The following is an extract from The Reluctant Traveller, Journal of a fishing widow by Sandra Armishaw (2008)

Wednesday, 5th March, 2008 was the fifth day of our stay at the wild and remote camp of Bush Betta, high in the arid hills of the Cauvery Wildlife Division, near Mekhedaatu. Our open-sided thatched hut looked down onto the silver-gold River Cauvery, 150ft. below, which flowed restlessly over pink granite bedrock on its journey towards the Tamil Nadu plains, and onwards to the Bay of Bengal. In the changing river, 'mugger' crocodiles, and mighty Mahseer swim side by side, hidden in its mysterious depths from the sight of anglers whose quest it is to capture this spectacular fish. Wednesday, 5th March, 2008 was the fifth day of our stay at the wild and remote camp of Bush Betta, high in the arid hills of the Cauvery Wildlife Division, near Mekhedaatu. Our open-sided thatched hut looked down onto the silver-gold River Cauvery, 150ft. below, which flowed restlessly over pink granite bedrock on its journey towards the Tamil Nadu plains, and onwards to the Bay of Bengal. In the changing river, 'mugger' crocodiles, and mighty Mahseer swim side by side, hidden in its mysterious depths from the sight of anglers whose quest it is to capture this spectacular fish.

Our host, a charismatic Indian Prince by the name of Nawabzada Mohammed Saad Bin Jung, promised us a visit to the Festival of Shiva, a vibrant celebration of one of the principal deities of the Hindu faith. Our host, a charismatic Indian Prince by the name of Nawabzada Mohammed Saad Bin Jung, promised us a visit to the Festival of Shiva, a vibrant celebration of one of the principal deities of the Hindu faith.

At four o'clock in the afternoon, our party of eight, and two tribal guides, climbed into two TATA 4x4's and set off down the steep, rocky road to the temple, an hour's drive away. It was hot and dusty as the heat of the day subsided, and we were glad of the air-conditioning and the tinted windows which filtered the sun's fierce rays and shaded our eyes.

As the camp faded into the background, I was wholly unaware that my perception of life, and all that was important to me was about to change forever. As the camp faded into the background, I was wholly unaware that my perception of life, and all that was important to me was about to change forever.

On the way to our destination, we passed crowds of Indian people - entire families. The women were dressed in vividly-coloured saris, which glowed with gold and silver; iridescent in the late afternoon sun. Most men appeared to be wearing T shirts, or Manchester United football shirts and scarves, reminding us that Westernisation is already present in India's ancient culture. Their enjoyment of the Festival was clear; I've never seen so many happy faces, eyes straining with curiosity to catch a glimpse of the white-skinned Europeans who passed them by.

People had travelled from far and wide to join in the celebrations; many were bare-footed, and there was an astonishing procession of scooters, bikes, and battered old yellow buses, the tyres of which were completely bald. People were packed inside like sardines in a tin, and they grinned widely as they hurtled around the countryside, on, or in their various modes of transport. It seems People had travelled from far and wide to join in the celebrations; many were bare-footed, and there was an astonishing procession of scooters, bikes, and battered old yellow buses, the tyres of which were completely bald. People were packed inside like sardines in a tin, and they grinned widely as they hurtled around the countryside, on, or in their various modes of transport. It seems  there are few rules when driving in India. People propel their vehicles towards each other at great speed, sound their horns, and swerve at the last moment. The result of this causes visitors like us, to gasp in horror and choke on the clouds of pink dust thrown up into the dry air, which on a late Indian winter's afternoon in March, is an energy-draining 45 degrees C. in the shade. there are few rules when driving in India. People propel their vehicles towards each other at great speed, sound their horns, and swerve at the last moment. The result of this causes visitors like us, to gasp in horror and choke on the clouds of pink dust thrown up into the dry air, which on a late Indian winter's afternoon in March, is an energy-draining 45 degrees C. in the shade.

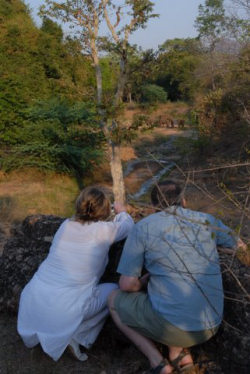

Our first unscheduled stop was at a strategic clearing in the hope of seeing wild elephants, and we were not disappointed. As the group disembarked from our vehicles, our guide gestured for us to crouch down in silence; he'd spotted some movement on the far bank of the shallow valley, where a small stream trickled through. There was intense excitement as we strained our eyes to see, but the small group of elephants was so well-camouflaged that it was only the gentle flapping of an ear, and the almost imperceptible twitch of a tail, which betrayed their presence. My friend and I whispered breathlessly  to each other, in awe of what we were witnessing, and our stillness was rewarded as the group of elephants, having detected us, began to move off into the safety of the deep forest. Eyes still searching, we spotted the gleaming white tusks of a young bull elephant, which stood stark against the verdant green of the trees. Then, whilst we looked on in amazement, our euphoria was ended by the wild gesturing of our guide; he'd located a second group of elephants in the valley below. to each other, in awe of what we were witnessing, and our stillness was rewarded as the group of elephants, having detected us, began to move off into the safety of the deep forest. Eyes still searching, we spotted the gleaming white tusks of a young bull elephant, which stood stark against the verdant green of the trees. Then, whilst we looked on in amazement, our euphoria was ended by the wild gesturing of our guide; he'd located a second group of elephants in the valley below.

Excited at the prospect of seeing more, my friend and I rushed, as noiselessly as possible, with dry twings crackling beneath our feet, to a vantage point behind a hugh granite boulder. Crouching behind the rock, our eyes scanned the near distance, and to our delight, we saw a spectacular sight - a group of five adult elephants and two calves at the waterhole. They stood close to each other, and as we watched, one young cow contentedly sprayed water over her back, apparently unaware of our presence. Or so  we thought. Without warning, the matriarch trumpeted an alarm, which sounded like the breathtaking roar of a tiger as it stalks the jungle at night, hunting for prey. It was spine-tingling. we thought. Without warning, the matriarch trumpeted an alarm, which sounded like the breathtaking roar of a tiger as it stalks the jungle at night, hunting for prey. It was spine-tingling.

At dinner the previous evening, Saad told us that wild elephants are amongst the most dangerous animals in the jungle, capable of tearing human-beings limb from limb! He also said that they're highly intelligent creatures with excellent communication skills, and this was in the fore-front of my mind when the terrifying sound filled the air.

I've heard elephants trumpeting in captivity, but nothing compares with the tiger-like 'roar' of a truly wild Indian elephant in its natural habitat. More worrying was the fact that the fearsome sound was immediately returned by another elephant hidden in trees close by. As the deafening roar echoed through the valley, I truly believed we were surrounded. (Saad said that elephants sometimes use a tactic known as the 'pincer-movement' - Zulus refer to this as 'the horns of the buffalo' - where two or more members of the group move silently around and behind their enemy, closing off any escape route. Unsurprisingly, people rarely survive such an attack by elephants).

This incident reminded me that we were the vulnerable ones in the jungle, and we needed no second warning as we sprinted back to the relative safety of our waiting vehicles. Once inside, we breathed a huge sigh of relief, and laughed nervously as we were driven at speed along the bumpy road, our cars dodging the sacred cows which wandered freely amongst the throngs of people on their way to the Festival. Everyone on the road seemed oblivious to the elephants, and the potential danger they were in because of their nearness to the herd.

As we headed for our final destination, we chattered in exhilaration about the experience of seeing elephants in the wild, but our conversation ended when we arrived at a small village in the middle of nowhere. It appeared to have emerged from the bowels of the barren earth. The long, straight road bisected small, brightly-coloured houses which had corrugated iron rooftops. The modest buildings are home to a small number of villagers whose simple way of life was to have a profound effect, causing me to question my Western values. As we headed for our final destination, we chattered in exhilaration about the experience of seeing elephants in the wild, but our conversation ended when we arrived at a small village in the middle of nowhere. It appeared to have emerged from the bowels of the barren earth. The long, straight road bisected small, brightly-coloured houses which had corrugated iron rooftops. The modest buildings are home to a small number of villagers whose simple way of life was to have a profound effect, causing me to question my Western values.

The road through the small village was flat and dusty, with concrete gullies running parallel, to drain away water and waste. Tribals (as the indigenous people are known) appeared to be walking or riding in both directions, each with a sense of purpose; like ants around a nest. The road through the small village was flat and dusty, with concrete gullies running parallel, to drain away water and waste. Tribals (as the indigenous people are known) appeared to be walking or riding in both directions, each with a sense of purpose; like ants around a nest.

I watched the beautiful elegance of a young Indian woman as she  carried a two-litre plastic water bottle, finely-balanced on her head. Members of our group photographed the village children and their modest homes, and I noticed a sign drawn in white on a newly-swept terrace made from cow dung. It said 'Welcome' in Hindi. carried a two-litre plastic water bottle, finely-balanced on her head. Members of our group photographed the village children and their modest homes, and I noticed a sign drawn in white on a newly-swept terrace made from cow dung. It said 'Welcome' in Hindi.

From the corner of my eye, I saw Saad seated on the ground; he was at ease as he greeted and chatted to an old friend. I stood in silence. All I could see were smiling faces. Then, without warning, I began to cry. Strangely overwhelmed, and embarrassed by my emotion, I lowered my head and quietly walked back to the privacy of the waiting jeep. Once inside, I struggled to hide my tears and Saad, who by then was sitting in the driver's seat, turned to look at me, a puzzled expression on his face.

'Why are you crying?' he asked, and before I could answer said: 'I hope you're not crying for those children?' and somewhat selfishly, I replied that I wasn't - I was crying for me. He didn't understand, so I said: 'They have so little and are happy.' I, on the other hand, have so much in comparison but have never found the true hapiness I could see in their faces; and I knew in my heart that they, as yet untainted by Western capitalism have far greater riches than I can ever hope for - an apparent inner peace and contentment; a life without mobile 'phones, flat-screen televisions, and the latest 'must have' gadgets which Westerners consider a necessity. That realisation was a revelation to me, and as we drove on to the Festival, I was still weeping. I knew then that my life would never be the same again, and I felt truly humbled. Little did I know that the visit to Shiva's temple would reinforce my earlier experiences, and had the potential to change my life irrevocably.

Sandra Armishaw

May 2008

(Photographs, courtesy of Reg Talbot, Sandra Armishaw and Peter Smith)

Shiva's Festival

The above photographs are a small selection from the Festival; I have included them here to give a flavour of the people and their culture.

Lord Shiva is one of the principal deities of the Hindu faith, and each year, people travel from far and wide to celebrate the cycle of death, destruction and rebirth which his Festival marks. Indeed, Shiva is known as The Destroyer. The other principal deities are Brahma, the Creator and Vishnu, the Maintainer.

Legend has it that his wife, who has several names; Sati, Shakti or Parvati (the consort of each principal Deity), was the love of his life. Her father did not approve of her marriage to Shiva, so disowned her, inviting everyone a family gathering, from which he excluded Shiva and Shakti. Determined not be shunned by her own father, she went alone to the event, but was ridiculed by her father. In her shame at being turned away, she committed suicide.

When Shiva discovered what had happened to his beloved wife, in his rage, he cut off her father's head. Picking up Shakti's body, Shiva placed it on his trident, which is his symbolic weapon, and began a dance of destruction throughout the universe. The people were terrified, and implored Brahma and Vishnu to stop the dance; a disc was thrown at Shiva, which cut Shakti's body into many parts and they fell to earth. In legend, a temple was built on the site where each part landed.

The intense atmosphere of that Festival is so difficult to convey through words, and it is for this reason that Part Two of Shiva's Festival still remains unwritten.

Sandra Armishaw

August, 2008

|